There’s an old proverb that says: “It’s better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness.” And what could be truer than that? Instead of despairing over a problem you see, take whatever small action you can to make things better – or, in the case of Becca Stevens, founder of Thistle Farms, start small and just get bigger and bigger, helping more and more people. Stevens started with a desire to help women who have been trapped in the dark world of trafficking, drug abuse, and sex work, and has ended up, more than two decades later, with not only a series of residential homes that get women off the streets, but also a successful business that sells candles and body care products, run by and benefiting the women who need it most.

“That Horrible and Hard Ground”

Becca Stevens’ own journey began in a dark and difficult place. When she was just five years old, her father, an Episcopal minister (Stevens herself is an Episcopal priest), was killed by a drunk driver, and the man who stepped in to help their family, the head of the church elders, began to sexually assault her. The abuse went on for years, but instead of breaking her, it flipped a switch of compassion in her, and gave her a drive to brighten the lives of others.

As she told us in an email: “That horrible and hard ground: that’s where the seeds were sown to do the work of Thistle Farms. Looking back now, a half a century later, I can see with the clarity of hindsight the wonders of my resiliency and compassion, not in spite of what happened, but in part because of what happened.”

Fast forward to 1994, and Stevens was working with vulnerable women in Nashville, in shelters and through ministry on the streets, women who she would discover she had a deep connection with, despite their very different backgrounds. They shared a painful history of exploitation – some studies suggest that well more than half of women working as prostitutes were sexually assaulted as children, and according to Thistle Farms’ website, “Most of the women we serve first experienced sexual abuse between ages 7-11, began using alcohol or drugs by age 13, and first hit the streets between the ages of 14 and 16.”

But it was something more than that: “When I began working with women coming off the streets and out of prison, I quickly learned I was meeting myself. These women and I had similar imperfect qualities that I found endearing and beautiful. I was free to laugh and share with them in a way I couldn’t with any other group of friends. Early on, I knew I was doing the work alongside survivors, not for survivors.”

Stevens began to seriously think about opening a two-year residential “sanctuary” for women looking for a way out of trafficking, drug abuse, and prostitution – after all, some studies show that up to 80% of women in prostitution report current or past homelessness – but it never seemed to be the right time. Then she got what she feels was the sign – literally – she needed to move forward.

“The idea of opening a two-year free sanctuary for women survivors had been simmering for years. But with the demands of work and a growing family that idea was just sitting on the back burner. Then late one afternoon in 1994, I was leaving work and putting my four-year-old son in the car seat when he looked up at me and asked, ‘Momma, why is that lady smiling?’ The billboard he could see was a huge image of a stripper in a catsuit, smiling. The question broke my heart, because I knew one day he wouldn’t ask it. The sign would just fade into the landscape where women are bought and sold without notice. On that day I felt a fire burning in my chest and knew I needed to open the first home for women who have survived lives of trafficking, addiction and prostitution.”

“It Takes a Community to Welcome Them Home”

So, in 1997, Becca Stevens started Thistle Farms with one residential home where five women with histories of prostitution, drug abuse, and trafficking came to live together and begin the hard work of transitioning from struggling to survive to living empowered lives of their own choosing. The organization has since expanded to include five residential communities in Nashville, which provide various services for the women that take part, such as medical and dental care, therapy, substance abuse treatment, legal help, and education.

This housing program has helped to transform the lives of more than 200 women, with 75% of graduates living “healthy, financially independent” lives, and Thistle Farms now also has 92 sister organizations, offering more than 500 beds for women who need them. And what makes their residential programs so unique? They are completely survivor-led, with no “authority figures” living in the house and running them; these homes are truly communities for the women who live in them.

As Stevens told CNN (she is a Top CNN Hero for 2016), “None of the women ended up on the streets by themselves. And so it makes sense that it takes a community to welcome them home.”

And while Stevens’ overarching philosophy for the work she does has always been that “love heals,” she also saw that when you have to struggle to survive, you can’t really live. You need the practical things in life, like a safe place to lay your head at night and a steady paycheck, which can also go a long way toward giving you the confidence you need to get back on your feet, and allowing you to make your own choices in life. The women she was working with couldn’t get jobs because of their criminal histories, so she took matters into her own hands, and began the social enterprise side of Thistle Farms, a company making candles and bath and body care products.

“[The first five women in the residential program] changed my understanding of what love looks like. In the beginning, it was all about keeping the bills paid, getting women to the doctor and therapist, doing outreach on the streets and jail, and building relationships in the community. We began the social enterprise part in 2001 because the residents were doing great, but couldn’t get jobs because of their criminal history. There is no long-term healing without economic independence so we started making candles and body balms in a small church kitchen to provide women [with] income.”

Why body care products? “It made perfect sense to me to make body care products that were about healing bodies – bodies that had been used and abused for so long,” she told CNN.

These days, Thistle Farms has grown to a $2 million business that helps fuel the nonprofit; it employs more than 75 people, two-thirds of whom are graduates of the residential program, and the products are sold in more than 500 stores. “The women have built the business. They run sales, accounting, manufacturing, shipping, and they keep growing the company so that more women can come through and be a part of it.”

“Something to Embrace and See Beauty In”

When asked about the name “Thistle Farms,” Becca Stevens told CNN, “I love thistles. Some (people) think of them as a noxious weed, and yet they have this beautiful purple and deep center. When we were going down to meet the women on the streets, that was the last wildflower that was there. So it made sense to name our company after it and remind us all that something to be discarded is (also) something to embrace and see beauty in.”

What grew out of Stevens’ “horrible and hard” experience, for her, is not just something to be discarded, but something that has given her the drive to change the lives of others who have walked that same ground., and not been so fortunate. And there is no judgement, no asking “What did you do?” to get where you are, just a shared sense of humanity; no one is left behind or forgotten.

For example, Stevens told us the story of Ty: “Her experience of sexual assault started with a family member in middle school. She quickly ended up on the streets and the way she tells her story is that when other girls were thinking about what dress to get for their prom, she was trying to figure out which cars to get in and out of. She was running drugs too, for her pimp, and was involved in a sting. She came to us directly from prison and was doing really well. But she still had one charge pending and about a year after she started with us she got sentenced to fourteen more years.

It took a lot of advocacy and work but she came back to our community after three years and was completely free of addiction. She got married and had a child with her husband. These days she directs the manufacturing at Thistle Farms. When the women come in she trains them to make these beautiful lavish products – candles and healing oils. She’s a joy and is completely fearless.”

To hear more from the graduates and employees of Thistle Farms in their own words, check out their stories here. There is much to learn from them, and one of the most powerful lessons is how similar we all are. As Becca Stevens points out, “Truly, the lines that separate any of us are thin. There’s so much more that we hold in common, and we are better when we all come together.”

To learn more about Thistle Farms, and to find out how you can help or how to purchase their products, go to their website. To donate, click here.

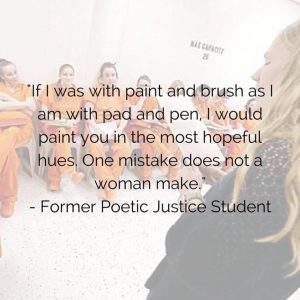

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”